What is a School if not a Promise? Interview with dpr-barcelona

Ethel Baraona Pohl and César Reyes Nájera are the founders of dpr-barcelona, a research studio and publishing practice based in Barcelona whose work deals with the threshold between architecture and social, political and economic issues. As well as publishing and research, they also curate exhibitions and projects part of their practice. In this interview, they offer their thoughts on invisible sources of knowledge, fun as a learning methodology and their own notion of the school as a promise.

As publishers with an architectural focus, how do you approach the process of not only deriving knowledge about the urban context but also disseminating that knowledge?

EBP: We feel a multiplicity of sources of knowledges is important: books, interviews, field trips… There is no single way – all of them are interconnected. You can acquire some knowledge by reading a book, but you can then expand that by interacting with the local community. The city is such a complex field that you cannot encapsulate the myriad different ways through which you learn about it.

CRN: The process appears definable within the structure of an educational system but as soon as you detach from that frame, it becomes clear just how complex a it is – and that it can be experienced and disseminated in several ways. Last year we contributed a piece to Volume magazine about trap music (a variation of rap) in Barcelona. In it, we explored the fact that there is a huge amount of information about how the city works contained within the lyrics of trap music. That is something that is largely invisible and beyond the “radar” of the education system. Trap has an interesting way of explaining the reality of the city and also of disseminating that knowledge.

EBP: And it’s spread via YouTube videos, which are often shot in the urban realm. Both the visuals and the lyrics are ways of learning about places never visited, perhaps on the periphery. These formats are very valuable ways of disseminating knowledge.

Several discussions during the Making Futures programme have touched on the idea that rather than teaching students about the city, it’s most meaningful to lead them to an understanding of their own place within it. How do you relate to that approach?

CRN: This is certainly a powerful idea. But sometimes it might difficult for you as a student to identify your agency within the city – especially if you are a newcomer, as it often happens with field trips. Here you need a disposition to allows you to become affected by the surrounding environment and the consciousness that your interactions affect it back – no matter how brief they are. For this, it is much better to be guided first by your emotions and then by your intellectual background.

EBP: Yes, emotions as facilitators of interactions. Here we can recall the relationship between the city and music, as a tool for triggering emotions. For instance, just before we initiated the Parasitic Reading Room [LINK] in Istanbul, we encountered the radioee mobile broadcasting from the streets of the city. They were interviewing a couple of rappers that at some point started to perform. This rap music moment was simultaneously a moment of learning for all of us. Even we as students, who were attentively listening and following the situation, weren’t able to understand all the words. Our curiosity was stimulated and we tried to understand the complexity of the situation when one of the local hosts explained us that the rap lyrics were meant to be denouncing the eviction and displacement of Romanies in the city. This music is one way of provoking a reaction and evoking curiosity as to why is this is happening. And when you are curious, you are more sensitive to learning.

CRN: Perhaps it is more connected to the use of certain tools, because you cannot simply say “go and experience this”; in learning you need an objective or goal. One of the tools that has been somehow forgotten in education is fun. The ability to have and learn through fun is something common to almost all humans from childhood. Perhaps we need to develop tools to allow all of us to have fun in urban space – and feel invited to do so. Many already exist; it’s about finding ways of using them.

Making Futures has also focused upon learning environments or sources of knowledge that transcend or exist beyond institutional boundaries, where process is as important (if not more), than outcome. You too have described “poems, films, Instagram photos, songs, email exchanges, objects, conversations with friends over a glass of wine or a coffee, dreams as things you learn from “albeit [or often because] the hectic diversity of formats, and sometimes its lack of seriousness.” How does this approach work in practice, in both institutional and non-institutional contexts?

EBP: One of the benefits of, for example, having fun during the process is that you will are more likely to repeat it. That way, the learning process exists not only within the framework of a particular workshop or format but endures beyond it. It’s like a muscle that needs to be exercised; if you get bored you don’t want to do it again, but if you are having fun then the learning process itself becomes something very positive.

CRN: There is also the potential of the affect, the spreading of the “will” to have fun. It’s a strategy of learning that should be paired with the conscious task of documenting the process in order to replicate it; not to exactly copy it, but to adapt it to another context.

EBP: There are always cycles within the institution: you create, the institution co-opts that, and then you create something anew as a reaction. I prefer to think about it acting as a “contagion”; we are so deeply interconnected that the institution is already contaminated without noticing it. An institution may appear to be retaining the same rigid structure but inside something different is happening at the same time.

CRN: There is also the idea that we take from the Argentinian collective Iconoclasistas: that institutions are not able to prevent what they are not able to imagine. Institutions are good at using formative processes in order to achieve a goal, but sometimes there is a lack of imagination. But maybe they don’t need imagination – this can comes from other agents – and instead just need to be able to replicate all these new strategies, providing the conditions for and being receptive towards the unexpected strategies or experiences that might occur.

And what about your own addition to the biennale programme, acting as another agent within it: the Parasitic Reading Room. How does reading as a practice and the position of being parasitic operate as mode of engagement?

EBP: We say reading as a practice because if not, there is no sense in making books. Nowadays, work and life take place within a sphere where everything is moving faster than ever before and these moments of reading are a gift of space and time, as well as an opportunity to care for the other. We think of books or Instagram posts or music – anything you can read – as ways to enjoy these small moments of slowness with others: reading together as a practice. It’s communion

CRN: And parasitic because within the field of intellectual production, there is a sense of originality and ownership that we always find problematic because no one of us is the result of an isolated flame. Instead, we are the result of interactions, experiences and readings, all of which build what you are – just as our bodies are not “just” human, but a mesh of bacteria and viruses.

Finally, to ask your own question – also contained within the parasitic reader – back to you: what is a school if not a promise?

EBP: This emerged when we were developing the concept of the Parasitic Reading Room for the biennale’s open call and reflecting on the term “school”. I remembered that every time I started studying something, it felt like a promise of something that will happen in the future – knowledge, encounters – it’s always a promise.

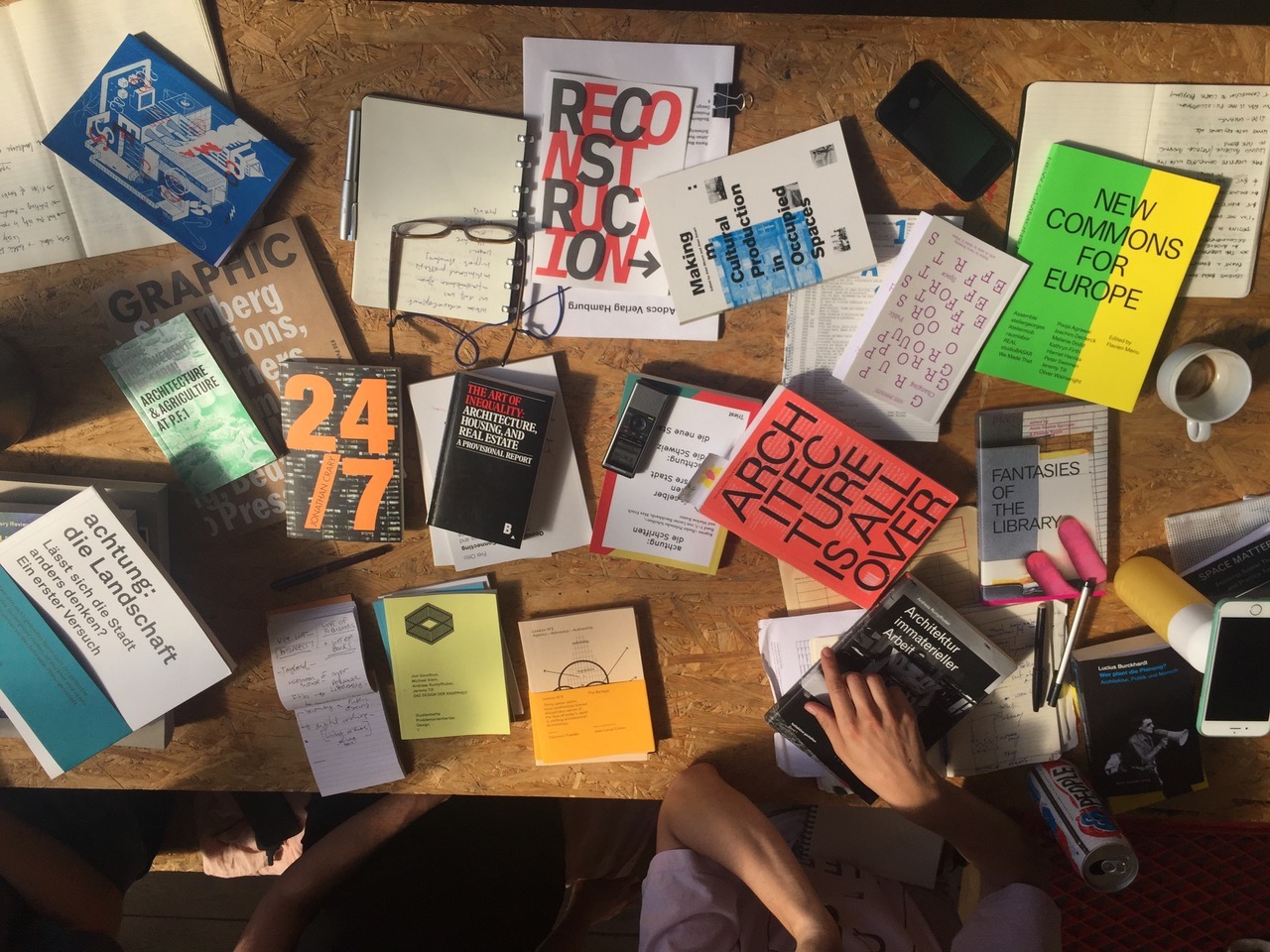

Ethel Baraona Pohl and César Reyes Nájera are the founders of dpr-barcelona, an architectural research practice dealing with three main lines: publishing, criticism and curating. We invited Ethel and César to join the Making Futures “Engaged Education” Mobile Workshop that took place in Istanbul, Turkey in September 2018. Picture by Lena Giovanazzi